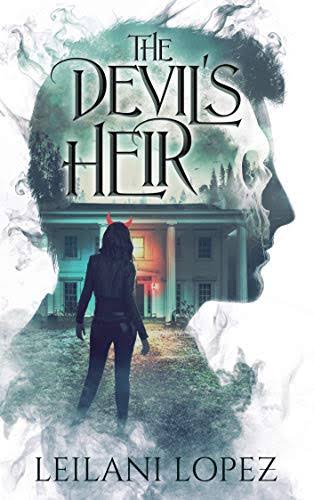

The Devil’s Heir

|

| The Devil’s Heir story |

There once was a good old canon of Notre Dame de Paris, who lived in a

fine house of his own, near St. Pierre-aux-Boeufs, in the Parvis. This

canon had come a simple priest to Paris, naked as a dagger without its

sheath. But since he was found to be a handsome man, well furnished

with everything, and so well constituted, that if necessary he was able to

do the work of many, without doing himself much harm, he gave himself

up earnestly to the confessing of ladies, giving to the melancholy a gentle

absolution, to the sick a drachm of his balm, to all some little dainty. He

was so well known for his discretion, his benevolence, and other

ecclesiastical qualities, that he had customers at Court. Then in order not

to awaken the jealousy of the officials, that of the husbands and others,

in short, to endow with sanctity these good and profitable practices, the

Lady Desquerdes gave him a bone of St. Victor, by virtue of which all the

miracles were performed. And to the curious it was said, "He has a bone

which will cure everything;" and to this, no one found anything to reply,

because it was not seemly to suspect relics. Beneath the shade of his

cassock, the good priest had the best of reputations, that of a man valiant

under arms. So he lived like a king. He made money with holy water;

sprinkled it and transmitted the holy water into good wine. More than

that, his name lay snugly in all the et ceteras of the notaries, in wills or in

caudicils, which certain people have falsely written CODICIL, seeing that

the word is derived from cauda, as if to say the tail of the legacy. In fact,

the good old Long Skirts would have been made an archbishop if he had

only said in joke, "I should like to put on a mitre for a handkerchief in

order to have my head warmer." Of all the benefices offered to him, he

chose only a simple canon's stall to keep the good profits of the

confessional. But one day the courageous canon found himself weak in

the back, seeing that he was all sixty- eight years old, and had held many

confessionals. Then thinking over all his good works, he thought it about

time to cease his apostolic labours, the more so, as he possessed about

one hundred thousand crowns earned by the sweat of his body. From that

day he only confessed ladies of high lineage, and did it very well. So that

it was said at Court that in spite of the efforts of the best young clerks there was still no one but the Canon of St. Pierre-aux-Boeufs to properly

bleach the soul of a lady of condition. Then at length the canon became

by force of nature a fine nonagenarian, snowy about the head, with

trembling hands, but square as a tower, having spat so much without

coughing, that he coughed now without being able to spit; no longer

rising from his chair, he who had so often risen for humanity; but drinking

dry, eating heartily, saying nothing, but having all the appearance of a

living Canon of Notre Dame. Seeing the immobility of the aforesaid

canon; seeing the stories of his evil life which for some time had

circulated among the common people, always ignorant; seeing his dumb

seclusion, his flourishing health, his young old age, and other things too

numerous to mention--there were certain people who to do the

marvellous and injure our holy religion, went about saying that the true

canon was long since dead, and that for more than fifty years the devil

had taken possession of the old priest's body. In fact, it seemed to his

former customers that the devil could only by his great heat have

furnished these hermetic distillations, that they remembered to have

obtained on demand from this good confessor, who always had le diable

au corps. But as this devil had been undoubtedly cooked and ruined by

them, and that for a queen of twenty years he would not have moved,

well-disposed people and those not wanting in sense, or the citizens who

argued about everything, people who found lice in bald heads, demanded

why the devil rested under the form of a canon, went to the Church of

Notre Dame at the hours when the canons usually go, and ventured so far

as to sniff the perfume of the incense, taste the holy water, and a

thousand other things. To these heretical propositions some said that

doubtless the devil wished to convert himself, and others that he

remained in the shape of the canon to mock at the three nephews and

heirs of this said brave confessor and make them wait until the day of

their own death for the ample succession of this uncle, to whom they paid

great attention every day, going to look if the good man had his eyes

open, and in fact found him always with his eye clear, bright, and piercing

as the eye of a basilisk, which pleased them greatly, since they loved

their uncle very much--in words. On this subject an old woman related

that for certain the canon was the devil, because his two nephews, the

procureur and the captain, conducting their uncle at night, without a

lamp, or lantern, returning from a supper at the penitentiary's, had

caused him by accident to tumble over a heap of stones gathered together to raise the statue of St. Christopher. At first the old man had

struck fire in falling, but was, amid the cries of his dear nephews and by

the light of the torches they came to seek at her house found standing up

as straight as a skittle and as gay as a weaving whirl, exclaiming that the

good wine of the penitentiary had given him the courage to sustain this

shock and that his bones were exceedingly hard and had sustained rude

assaults. The good nephews believing him dead, were much astonished,

and perceived that the day that was to dispatch their uncle was a long

way off, seeing that at the business stones were of no use. So that they

did not falsely call him their good uncle, seeing that he was of good

quality. Certain scandalmongers said that the canon found so many

stones in his path that he stayed at home not to be ill with the stone, and

the fear of worse was the cause of his seclusion.

Of all these sayings and rumours, it remains that the old canon, devil or

not, kept his house, and refused to die, and had three heirs with whom he

lived as with his sciaticas, lumbagos, and other appendage of human life.

Of the said three heirs, one was the wickedest soldier ever born of a

woman, and he must have considerably hurt her in breaking his egg,

since he was born with teeth and bristles. So that he ate, two-fold, for the

present and the future, keeping wenches whose cost he paid; inheriting

from his uncle the continuance, strength, and good use of that which is

often of service. In great battles, he endeavoured always to give blows

without receiving them, which is, and always will be, the only problem to

solve in war, but he never spared himself there, and, in fact, as he had no

other virtue except his bravery, he was captain of a company of lancers,

and much esteemed by the Duke of Burgoyne, who never troubled what

his soldiers did elsewhere. This nephew of the devil was named Captain

Cochegrue; and his creditors, the blockheads, citizens, and others, whose

pockets he slit, called him the Mau-cinge, since he was as mischievous as

strong; but he had moreover his back spoilt by the natural infirmity of a

hump, and it would have been unwise to attempt to mount thereon to get

a good view, for he would incontestably have run you through.

The second had studied the laws, and through the favour of his uncle had

become a procureur, and practised at the palace, where he did the

business of the ladies, whom formerly the canon had the best confessed.

This one was called Pille-grue, to banter him upon his real name, which was Cochegrue, like that of his brother the captain. Pille-grue had a lean

body, seemed to throw off very cold water, was pale of face, and

possessed a physiognomy like a polecat.

This notwithstanding, he was worth many a penny more than the captain,

and had for his uncle a little affection, but since about two years his heart

had cracked a little, and drop by drop his gratitude had run out, in such a

way that from time to time, when the air was damp, he liked to put his

feet into his uncle's hose, and press in advance the juice of this good

inheritance. He and his brother, the soldier found their share very small,

since loyally, in law, in fact, in justice, in nature, and in reality, it was

necessary to give the third part of everything to a poor cousin, son of

another sister of the canon, the which heir, but little loved by the good

man, remained in the country, where he was a shepherd, near

Nanterre.__

The guardian of beasts, an ordinary peasant, came to town by the advice

of his two cousins, who placed him in their uncle's house, in the hope

that, as much by his silly tricks and his clumsiness, his want of brain, and

his ignorance, he would be displeasing to the canon, who would kick him

out of his will. Now this poor Chiquon, as the shepherd was named, had

lived about a month alone with his old uncle, and finding more profit or

more amusement in minding an abbot than looking after sheep, made

himself the canon's dog, his servant, the staff of his old age, saying, "God

keep you," when he passed wind, "God save you," when he sneezed, and

"God guard you," when he belched; going to see if it rained, where the

cat was, remaining silent, listening, speaking, receiving the coughs of the

old man in his face, admiring him as the finest canon there ever was in

the world, all heartily and in good faith, knowing that he was licking him

after the manner of animals who clean their young ones; and the uncle,

who stood in no need of learning which side the bread was buttered,

repulsed poor Chiquon, making him turn about like a die, always calling

him Chiquon, and always saying to his other nephews that this Chiquon

was helping to kill him, such a numskull was he. Thereupon, hearing this,

Chiquon determined to do well by his uncle, and puzzled his

understanding to appear better; but as he had a behind shaped like a pair

of pumpkins, was broad shouldered, large limbed, and far from sharp, he

more resembled old Silenus than a gentle Zephyr. In fact, the poor shepherd, a simple man, could not reform himself, so he remained big

and fat, awaiting his inheritance to make himself thin.

One evening the canon began discoursing concerning the the devil and

the grave agonies, penances, tortures, etc., which God will get warm for

the accursed, and the good Chiquon hearing it, began to open his eyes as

wide as the door of an oven, at the statement, without believing a word of

it.

"What," said the canon, "are you not a Christian?"

"In that, yes," answered Chiquon.

"Well, there is a paradise for the good; is it not necessary to have a hell

for the wicked?"

"Yes, Mr. Canon; but the devil's of no use. If you had here a wicked man

who turned everything upside down; would you not kick him out of

doors?"

"Yes, Chiquon."

"Oh, well, mine uncle; God would be very stupid to leave in the this

world, which he has so curiously constructed, an abominable devil whose

special business it is to spoil everything for him. Pish! I recognise no devil

if there be a good God; you may depend upon that. I should very much

like to see the devil. Ha, ha! I am not afraid of his claws!"

"And if I were of your opinion I should have no care of my very youthful

years in which I held confessions at least ten times a day."

"Confess again, Mr. Canon. I assure you that will be a precious merit on

high."

"There, there! Do you mean it?"

"Yes, Mr. Canon."

"Thou dost not tremble, Chiquon, to deny the devil?"

"I trouble no more about it than a sheaf of corn."

"The doctrine will bring misfortune upon you."

"By no means. God will defend me from the devil because I believe him

more learned and less stupid than the savans make him out."

Thereupon the two other nephews entered, and perceiving from the voice

of the canon that he did not dislike Chiquon very much, and that the

jeremiads which he had made concerning him were simple tricks to

disguise the affection which he bore him, looked at each other in great

astonishment.

Then, seeing their uncle laughing, they said to him--

"If you will make a will, to whom will you leave the house?

"To Chiquon."

"And the quit rent of the Rue St. Denys?"

"To Chiquon."

"And the fief of Ville Parisis?"

"To Chiquon."

"But," said the captain, with his big voice, "everything then will be

Chiquon's."

"No," replied the canon, smiling, "because I shall have made my will in

proper form, the inheritance will be to the sharpest of you three; I am so

near to the future, that I can therein see clearly your destinies."

And the wily canon cast upon Chiquon a glance full of malice, like a decoy

bird would have thrown upon a little one to draw him into her net. The fire of his flaming eye enlightened the shepherd, who from that moment

had his understanding and his ears all unfogged, and his brain open, like

that of a maiden the day after her marriage. The procureur and the

captain, taking these sayings for gospel prophecies, made their bow and

went out from the house, quite perplexed at the absurd designs of the

canon.

"What do you think of Chiquon?" said Pille-grue to Mau-cinge.

"I think, I think," said the soldier, growling, "that I think of hiding myself

in the Rue d'Hierusalem, to put his head below his feet; he can pick it up

again if he likes."

"Oh, oh!" said the procureur, "you have a way of wounding that is easily

recognised, and people would say 'It's Cochegrue.' As for me, I thought to

invite him to dinner, after which, we would play at putting ourselves in a

sack in order to see, as they do at Court, who could walk best thus

attired. Then having sewn him up, we could throw him into the Seine, at

the same time begging him to swim."

"This must be well matured," replied the soldier.

"Oh! it's quite ripe," said the advocate. "The cousin gone to the devil, the

heritage would then be between us two."

"I'm quite agreeable," said the fighter, "but we must stick as close

together as the two legs of the same body, for if you are fine as silk, I as

strong as steel, and daggers are always as good as traps-- you hear that,

my good brother."

"Yes," said the advocate, "the cause is heard--now shall it be the thread

or the iron?"

"Eh? ventre de Dieu! is it then a king that we are going to settle? For a

simple numskull of a shepherd are so many words necessary? Come!

20,000 francs out of the Heritage to the one of us who shall first cut him

off: I'll say to him in good faith, 'Pick up your head.'" "And I, 'Swim my friend,'" cried the advocate, laughing like the gap of a

pourpoint.

And then they went to supper, the captain to his wench, and the advocate

to the house of a jeweller's wife, of whom he was the lover.

Who was astonished? Chiquon! The poor shepherd heard the planning of

his death, although the two cousins had walked in the parvis, and talked

to each other as every one speaks at church when praying to God. So

that Chiquon was much coupled to know if the words had come up or if

his ears had gone down.

"Do you hear, Mister Canon?"

"Yes," said he, "I hear the wood crackling in the fire."

"Ho, ho!" replied Chiquon, "if I don't believe in the devil, I believe in St.

Michael, my guardian angel; I go there where he calls me."

"Go, my child," said the canon, "and take care not to wet yourself, nor to

get your head knocked off, for I think I hear more rain, and the beggars

in the street are not always the most dangerous beggars."

At these words Chiquon was much astonished, and stared at the canon;

found his manner gay, his eye sharp, and his feet crooked; but as he had

to arrange matters concerning the death which menaced him, he thought

to himself that he would always have leisure to admire the canon, or to

cut his nails, and he trotted off quickly through the town, as a little

woman trots towards her pleasure.

His two cousins having no presumption of the divinatory science, of which

shepherds have had many passing attacks, had often talked before him of

their secret goings on, counting him as nothing.

Now one evening, to amuse the canon, Pille-grue had recounted to him

how had fallen in love with him a wife of a jeweller on whose head he had

adjusted certain carved, burnished, sculptured, historical horns, fit for the

brow of a prince. The good lady was to hear him, a right merry wench, quick at opportunities, giving an embrace while her husband was

mounting the stairs, devouring the commodity as if she was swallowing a

a strawberry, only thinking of love-making, always trifling and frisky, gay

as an honest woman who lacks nothing, contenting her husband, who

cherished her so much as he loved his own gullet; subtle as a perfume, so

much so, that for five years she managed so well with his household

affairs, and her own love affairs, that she had the reputation of a prudent

woman, the confidence of her husband, the keys of the house, the purse,

and all.

"And when do you play upon this gentle flute?" said the canon.

"Every evening and sometimes I stay all the night."

"But how?" said the canon, astonished.

"This is how. There is a room close to, a chest into which I get. When the

good husband returns from his friend the draper's, where he goes to

supper every evening, because often he helps the draper's wife in her

work, my mistress pleads a slight illness, lets him go to bed alone, and

comes to doctor her malady in the room where the chest is. On the

morrow, when my jeweller is at his forge, I depart, and as the house has

one exit on to the bridge, and another into the street, I always come to

the door when the husband is not, on the pretext of speaking to him of

his suits, which commence joyfully and heartily, and I never let them

come to an end. It is an income from cuckoldom, seeing that in the minor

expenses and loyal costs of the proceedings, he spends as much as on

the horses in his stable. He loves me well, as all good cuckolds should

love the man who aids them, to plant, cultivate, water and dig the natural

garden of Venus, and he does nothing without me."__

Now these practices came back again to the memory of the shepherd,

who was illuminated by the light issuing from his danger, and counselled

by the intelligence of those measures of self-preservation, of which every

animal possesses a sufficient dose to go to the end of his ball of life. So

Chiquon gained with hasty feet the Rue de la Calandre, where the jeweller

should be supping with his companion, and after having knocked at the

door, replied to question put to him through the little grill, that he was a messenger on state secrets, and was admitted to the draper's house. Now

coming straight to the fact, he made the happy jeweller get up from his

table, led him to a corner, and said to him: "If one of your neighbours had

planted a horn on your forehead and he was delivered to you, bound hand

and foot, would you throw him into the river?"

"Rather," said the jeweller, "but if you are mocking me I'll give you a

good drubbing."

"There, there!" replied Chiquon, "I am one of your friends and come to

warn you that as many times as you have conversed with the draper's

wife here, as often has your own wife been served the same way by the

advocate Pille-grue, and if you will come back to your forge, you will find

a good fire there. On your arrival, he who looks after your you- know-

what, to keep it in good order, gets into the big clothes chest. Now make

a pretence that I have bought the said chest of you, and I will be upon

the bridge with a cart, waiting your orders."

The said jeweller took his cloak and his hat, and parted company with his

crony without saying a word, and ran to his hole like a poisoned rat. He

arrives and knocks, the door is opened, he runs hastily up the stairs, finds

two covers laid, sees his wife coming out of the chamber of love, and then

says to her, "My dear, here are two covers laid."

"Well, my darling are we not two?"

"No," said he, "we are three."

"Is your friend coming?" said she, looking towards the stairs with perfect

innocence.

"No, I speak of the friend who is in the chest."

"What chest?" said she. "Are you in your sound senses? Where do you see

a chest? Is the usual to put friends in chests? Am I a woman to keep

chests full of friends? How long have friends been kept in chests? Are you

come home mad to mix up your friends with your chests? I know no other friend then Master Cornille the draper, and no other chest than the one

with our clothes in."

"Oh!," said the jeweller, "my good woman, there is a bad young man,

who has come to warn me that you allow yourself to be embraced by our

advocate, and that he is in the chest."

"I!" said she, "I would not put up with his knavery, he does everything

the wrong way."

"There, there, my dear," replied the jeweller, "I know you to be a good

woman, and won't have a squabble with you about this paltry chest. The

giver of the warning is a box-maker, to whom I am about to sell this

cursed chest that I wish never again to see in my house, and for this one

he will sell me two pretty little ones, in which there will not be space

enough even for a child; thus the scandal and the babble of those envious

of your virtue will be extinguished for want of nourishment."

"You give me great pleasure," said she; "I don't attach any value to my

chest, and by chance there is nothing in it. Our linen is at the wash. It will

be easy to have the mischievous chest taken away tomorrow morning.

Will you sup?"

"Not at all," said he, "I shall sup with a better appetite without the chest."

"I see," said she, "that you won't easily get the chest out of your head."

"Halloa, there!" said the jeweller to his smiths and apprentices; "come

down!"

In the twinkling of an eye his people were before him. Then he, their

master, having briefly ordered the handling of the said chest, this piece of

furniture dedicated to love was tumbled across the room, but in passing

the advocate, finding his feet in the air to the which he was not

accustomed, tumbled over a little.

"Go on," said the wife, "go on, it's the lid shaking." "No, my dear, it's the bolt."

And without any other opposition the chest slid gently down the stairs.

"Ho there, carrier!" said the jeweller, and Chiquon came whistling his

mules, and the good apprentices lifted the litigious chest into the cart.

"Hi, hi!" said the advocate.

"Master, the chest is speaking," said an apprentice.

"In what language?" said the jeweller, giving him a good kick between

two features that luckily were not made of glass. The apprentice tumbled

over on to a stair in a way that induced him to discontinue his studies in

the language of chests. The shepherd, accompanied by the good jeweller,

carried all the baggage to the water-side without listening to the high

eloquence of the speaking wood, and having tied several stones to it, the

jeweller threw it into the Seine.

"Swim, my friend," cried the shepherd, in a voice sufficiently jeering at

the moment when the chest turned over, giving a pretty little plunge like

a duck.

Then Chiqoun continued to proceed along the quay, as far as the Rue- du-

port, St Laudry, near the cloisters of Notre Dame. There he noticed a

house, recognised the door, and knocked loudly.

"Open," said he, "open by order of the king."

Hearing this an old man who was no other than the famous Lombard,

Versoris, ran to the door.

"What is it?" said he.

"I am sent by the provost to warn you to keep good watch tonight,"

replied Chiquon, "as for his own part he will keep his archers ready. The

hunchback who has robbed you has come back again. Keep under arms,

for he is quite capable of easing you of the rest." Having said this, the good shepherd took to his heels and ran to the Rue

des Marmouzets, to the house where Captain Cochegrue was feasting

with La Pasquerette, the prettiest of town-girls, and the most charming in

perversity that ever was; according to all the gay ladies, her glance was

sharp and piercing as the stab of a dagger. Her appearance was so

tickling to the sight, that it would have put all Paradise to rout. Besides

which she was as bold as a woman who has no other virtue than her

insolence. Poor Chiquon was greatly embarrassed while going to the

quarter of the Marmouzets. He was greatly afraid that he would be unable

to find the house of La Pasquerette, or find the two pigeons gone to roost,

but a good angel arranged there speedily to his satisfaction. This is how.

On entering the Rue des Marmouzets he saw several lights at the

windows and night-capped heads thrust out, and good wenches, gay girls,

housewives, husbands, and young ladies, all of them are just out of bed,

looking at each other as if a robber were being led to execution by

torchlight.

"What's the matter?" said the shepherd to a citizen who in great haste

had rushed to the door with a chamber utensil in his hand.

"Oh! it's nothing," replied the good man. "We thought it was the

Armagnacs descending upon the town, but it's only Mau-cinge beating La

Pasquerette."

"Where?" asked the shepherd.

"Below there, at that fine house where the pillars have the mouths of

flying frogs delicately carved upon them. Do you hear the varlets and the

serving maids?"

And in fact there was nothing but cries of "Murder! Help! Come some

one!" and in the house blows raining down and the Mau-cinge said with

his gruff voice:

"Death to the wench! Ah, you sing out now, do you? Ah, you want your

money now, do you? Take that--" And La Pasquerette was groaning, "Oh! oh! I die! Help! Help! Oh! oh!"

Then came the blow of a sword and the heavy fall of a light body of the

fair girl sounded, and was followed by a great silence, after which the

lights were put out, servants, waiting women, roysterers, and others went

in again, and the shepherd who had come opportunely mounted the stairs

in company with them, but on beholding in the room above broken

glasses, slit carpets, and the cloth on the floor with the dishes, everyone

remained at a distance.

The shepherd, bold as a man with but one end in view, opened the door

of the handsome chamber where slept La Pasquerette, and found her

quite exhausted, her hair dishevelled, and her neck twisted, lying upon a

bloody carpet, and Mau-cinge frightened, with his tone considerably

lower, and not knowing upon what note to sing the remainder of his

anthem.

"Come, my little Pasquerette, don't pretend to be dead. Come, let me put

you tidy. Ah! little minx, dead or alive, you look so pretty in your blood

I'm going to kiss you." Having said which the cunning soldier took her and

threw her upon the bed, but she fell there all of a heap, and stiff as the

body of a man that had been hanged. Seeing which her companion found

it was time for his hump to retire from the game; however, the artful

fellow before slinking away said, "Poor Pasquerette, how could I murder

so good of girl, and one I loved so much? But, yes, I have killed her, the

thing is clear, for in her life never did her sweet breast hang down like

that. Good God, one would say it was a crown at the bottom of a wallet.

Thereupon Pasquerette opened her eyes and then bent her head slightly

to look at her flesh, which was white and firm, and she brought herself to

life by a box on the ears, administered to the captain.

"That will teach you to beware of the dead," said she, smiling.

"And why did he kill you, my cousin?" asked the shepherd.

"Why? Tomorrow the bailiffs seize everything that's here, and he who has

no more money than virtue, reproached me because I wished to be

agreeable to a handsome gentlemen, who would save me from the hands

of justice. "Pasquerette, I'll break every bone in your skin."

"There, there!" said Chiquon, whom the Mau-cinge had just recognised,

"is that all? Oh, well, my good friend, I bring you a large sum."

"Where from?" asked the captain, astonished.

"Come here, and let me whisper in your ear--if 30,000 crowns were

walking about at night under the shadow of a pear-tree, would you not

stoop down to pluck them, to prevent them spoiling?"

"Chiquon, I'll kill you like a dog if you are making game of me, or I will

kiss you there where you like it, if you will put me opposite 30,000

crowns, even when it shall be necessary to kill three citizens at the corner

of the Quay."

"You will not even kill one. This is how the matter stands. I have for a

sweetheart in all loyalty, the servant of the Lombard who is in the city

near the house of our good uncle. Now I have just learned on sound

information that this dear man has departed this morning into the country

after having hidden under a pear-tree in his garden a good bushel of gold,

believing himself to be seen only by the angels. But the girl who had by

chance a bad toothache, and was taking the air at her garret window,

spied the old crookshanks, without wishing to do so, and chattered of it to

me in fondness. If you will swear to give me a good share I will lend you

my shoulders in order that you may climb on to the top of the wall and

from there throw yourself into the pear-tree, which is against the wall.

There, now do you say that I am a blockhead, an animal?"

"No, you are a right loyal cousin, an honest man, and if you have ever to

put an enemy out off the way, I am there, ready to kill even one of my

own friends for you. I am no longer your cousin, but your brother. Ho

there! sweetheart," cried Mau-cinge to La Pasquerette, "put the tables

straight, wipe up your blood, it belongs to me, and I'll pay you for it by

giving you a hundred times as much of mine as I have taken of thine.

Make the best of it, shake the black dog, off your back, adjust your

petticoats, laugh, I wish it, look to the stew, and let us recommence our evening prayer where we left it off. Tomorrow I'll make thee braver than

a queen. This is my cousin whom I wish to entertain, even when to do so

it were necessary to turn the house out of windows. We shall get back

everything tomorrow in the cellars. Come, fall to!"

Thus, and in less time than it takes a priest to say his Dominus vobiscum,

the whole rookery passed from tears to laughter as it had previously from

laughter to tears. It is only in these houses of ill- fame that love is made

with the blow of a dagger, and where tempests of joy rage between four

walls. But these are things ladies of the high-neck dress do not

understand.

The said captain Cochegrue was gay as a hundred schoolboys at the

breaking up of class, and made his good cousin drink deeply, who spilled

everything country fashion, and pretended to be drunk, spluttering out a

hundred stupidities, as, that "tomorrow he would buy Paris, would lend a

hundred thousand crowns to the king, that he would be able to roll in

gold;" in fact, talked so much nonsense that the captain, fearing some

compromising avowal and thinking his brain quite muddled enough, led

him outside with the good intention, instead of sharing with him, of

ripping Chiquon open to see if he had not a sponge in his stomach,

because he had just soaked in a big quart of the good wine of Suresne.

They went along, disputing about a thousand theological subjects which

got very much mixed up, and finished by rolling quietly up against the

garden where were the crowns of the Lombard. Then Cochegrue, making

a ladder of Chiquon's broad shoulders, jumped on to the pear-tree like a

man expert in attacks upon towns, but Versoris, who was watching him,

made a blow at his neck, and repeated it so vigorously that with three

blows fell the upper portion of the said Cochegrue, but not until he had

heard the clear voice of the shepherd, who cried to him, "Pick up your

head, my friend." Thereupon the generous Chiquon, in whom virtue

received its recompense, thought it would be wise to return to the house

of the good canon, whose heritage was by the grace of God considerably

simplified. Thus he gained the Rue St. Pierre-Aux-Boeufs with all speed,

and soon slept like a new-born baby, no longer knowing the meaning of

the word "cousin-german." Now, on the morrow he rose according to the

habit of shepherds, with the sun, and came into his uncle's room to

inquire if he spat white, if he coughed, if he had slept well; but the old servant told him that the canon, hearing the bells of St Maurice, the first

patron of Notre Dame, ring for matins, he had gone out of reverence to

the cathedral, where all the Chapter were to breakfast with the Bishop of

Paris; upon which Chiquon replied: "Is his reverence the canon out of his

senses thus to disport himself, to catch a cold, to get rheumatism? Does

he wish to die? I'll light a big fire to warm him when he returns;" and the

good shepherd ran into the room where the canon generally sat, and to

his great astonishment beheld him seated in his chair.

"Ah, ah! What did she mean, that fool of a Bruyette? I knew you were too

well advised to be shivering at this hour in your stall."

The canon said not a word. The shepherd who was like all thinkers, a man

of hidden sense, was quite aware that sometimes old men have strange

crotchets, converse with the essence of occult things, and mumble to

themselves discourses concerning matters not under consideration; so

that, from reverence and great respect for the secret meditations of the

canon, he went and sat down at a distance, and waited the termination of

these dreams; noticing, silently the length of the good man's nails, which

looked like cobbler's awls, and looking attentively at the feet of his uncle,

he was astonished to see the flesh of his legs so crimson, that it reddened

his breeches and seemed all on fire through his hose.

He is dead, thought Chiquon. At this moment the door of the room

opened, and he still saw the canon, who, his nose frozen, came back from

church.

"Ho, ho!" said Chiquon, "my dear Uncle, are you out of your senses?

Kindly take notice that you ought not to be at the door, because you are

already seated in your chair in the chimney corner, and that it is

impossible for there to be two canons like you in the world."

"Ah! Chiquon, there was a time when I could have wished to be in two

places at once, but such is not the fate of a man, he would be too happy.

Are you getting dim-sighted? I am alone here."

Then Chiquon turned his head towards the chair, and found it empty; and

much astonished, as you will easily believe, he approached it, and found on the seat a little pat of cinders, from which ascended a strong odour of

sulphur.

"Ah!" said he merrily, "I perceive that the devil has behaved well towards

me--I will pray God for him."

And thereupon he related naively to the canon how the devil had amused

himself by playing at providence, and had loyally aided him to get rid of

his wicked cousins, the which the canon admired much, and thought very

good, seeing that he had plenty of good sense left, and often had

observed things which were to the devil's advantage. So the good old

priest remarked that 'as much good was always met with in evil as evil in

good, and that therefore one should not trouble too much after the other

world, the which was a grave heresy, which many councils have put

right'.

And this was how the Chiquons became rich, and were able in these

times, by the fortunes of their ancestors, to help to build the bridge of St.

Michael, where the devil cuts a very good figure under the angel, in

memory of this adventure now consigned to these veracious histories .

0 Comments